When many voices come together, they create a sound so loud it moves you. What you hear when you experience this is the very same thing that gives a good choir the power to deliver you from your sins – a powerful element called resonance. When two frequencies stream in harmonic proportion to each other. Or in the case of this atelier, when the ideas of diverse people come together in a hum of productive chatter under the same roof at exactly the same time.

The roof in question sat atop a beautiful gazebo housed in Parque Vincentina Aranha in São Jose dos Campos, Brazil, just north of São Paulo. Parque Vincentina used to be a quarantine site of a hospice for tuberculosis suffers in the 1920s. Since then, it has been lovingly restored as one of the main public parks in the city. The grounds and buildings are beautifully landscaped in a fit-for-royalty fashion. You enter the park through a towering gold-paint encrusted steel gate. The path to the main park building is meticulously cleaned each day, and paved with careful craftmanship.

Gawking around corners throughout the park is a special speckled bird—the Galinha D’Angola (Helmeted Guinea Fowl), which I learned is a common variety of turkey in Brazil. A far cry from the time the grounds were used as a hospice, the beautiful exterior stone corridors and archways are now filled with footsteps and purpose as people saunter to and from throughout the day enjoying the park and the community programming the city organizes weekly. The Nature of Cities, ICLEI South America, the City of San Jose dos Campos, and a host of other international partners designed a public engagement workshop to gather local knowledge, and map community visioning and meaning of food, water, and energy innovations in São Jose dos Campos. This public engagement was supporting an international research project called IFWEN, which looks at how green and blue infrastructure in cities support innovations in integrating and governing food, water, and energy in a nexus approach. The goal of the workshop was to engage the community and design a collaborative space where the knowledge and social imaginaries of people living in the cities collided with those of the international scientists.

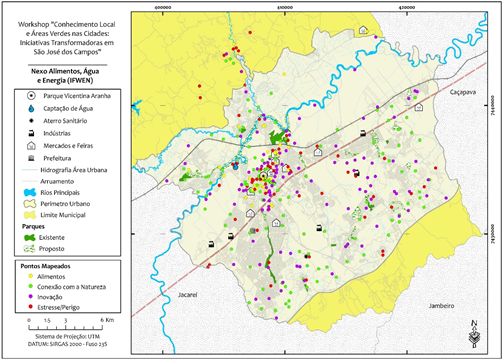

Community Mapping Exercise

We had 50 people joins us from the community in São Jose dos Campos, and they were all from very different walks of life. A few of them were teachers, two came from an eco-fashion label, and another handful were a mix of municipal officials, activists, children, and everyday citizens. The maps created by the community were rich in detail and experience. In total there were eight maps created. The picture below details both the satellite maps and the inner-city maps that community members used to highlight points of meaning along six question prompts we created based on the research focus of the international study. The data mapped was both tangible, such as the location of natural assets, roads, transport links etc., and intangible, such as place attachment, safety, belonging, stress and smells, etc., that exist in their city.

The maps were not only an opportunity for the international researchers to mobilize citizen science to better understand the context of city life in São José dos Campos, but it was also a learning experience for the community to have access to such rich physical details about their city from both the city database and the international team

Findings from the workshop

Energy Trade-offs Energy is a very visible issue area in São José dos Campos. due to the fact that the city has a sequence of high voltage towers that conduct electricity to the capital São Paulo. The transmission lines are imposing throughout its landscape. This was a point of contention for the city residence, and a common mentioned innovation was the desire for green infrastructure to be placed around the site of these towers to make the space useable and more pleasant for residence. The city has recently launched a project called Linha Verde to address this issue.

Water Contamination

Water was the most important element mapped on each of the eight community maps. Flooding in the inner-city region was a very big concern for most, along with a heightened sense of risk of industrial leaks, illegal dumping sites, poor soil quality and traffic pollution that cause water contamination in and around the city. Innovations centered around a desire for infrastructures that could facilitate greater river tourism, leisure sites for swimming and river revitalization to make fishing sites a possibility.

Food Sustainability

Overwhelmingly most community residences that participated in our work shop got their food from public markets more than super markets, although access to both was clearly important. São José dos Campos supplies the capital São Paulo with an important volume of food, as well as destines much of its agricultural production for export. This production comes from large agricultural producers, who represent an important part of the city’s economy. Residence expressed a desire to continue to innovate infrastructures for local food such as, community gardens, urban farming, and composting.

The workshop was noted by many community members and the scientists to have been a really inspiring collaborative space. Such a collaborative space is an important aspect of any research study, especially an international one. Where researchers strive to support knowledge gathering and exchange in cities, and not simply aim to extract data, their results are richer and the co-benefits for the community are empowering for capacity-building and innovation creation in cities.

Designing a public engagement

There are a few important aspects of collaborative design that we have found at The Nature of Cities, within our approach called the Forum for Radical Imagination on Environmental Cultures that make events that bring diverse groups together more or less successful depending on the goal of the engagement. The insights listed below can ultimately help researchers, urban planners, developers, municipal decision-makers and many other actors to meaningfully involve the public in city building.

Use the earth: Find a way to connect with nature

When you say, “a breath of fresh air”—consider the underlying meaning of this popular metaphor that appears in different forms in various cultures around the world. As humans, we often crave “a breath of fresh air” to incite a change of pace, regenerate, or help us think through something difficult. Nature has a way of humbling people. A stroll in the park, or a breath of fresh air grounds you and helps you clear your mind. Including nature as a key element to the design of a community engagement can support creative flows of discussion and inspiration—especially as you are bound to invite diverse peoples, personalities and partialities to work together towards a common goal. The end of September in Brazil is just the beginning of the summer months, so there was a good chance our hopes to host this event outside would be thwarted by rain. It did rain. But by then our discussions were well underway, and nobody really cared at that point.

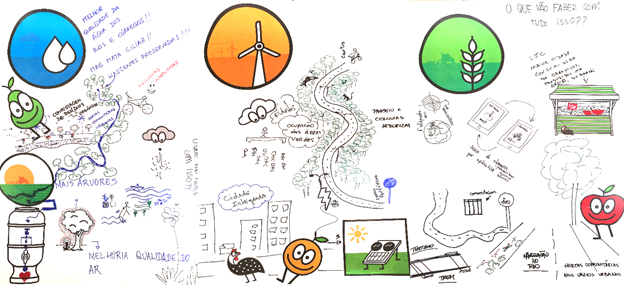

Draw from the arts: Materialize your ideas

Dialogue and discussion are important as an ideation stage, but its critical we carry those ideas through so that they can materialize into the changes we want to see in our cities. Art is an incredibly powerful capacity humans have that can help us achieve this. What is art? Often, we consider “art” to be the product or result of something we produced in a creative state of mind, like a painting or a film. Sure, it is. But we shouldn’t forget we are fundamentally talking about a process, or the expression of human creative skill and imagination, that sometimes manifests itself in a painting, but other times manifests itself in the scientist who is trying to decipher exactly what the numbers they tabulated mean. For our event, we began with dialogue and discussion. When we were all in this ideation stage, we were imagining. The Nature of Cities worked with a gallery in São Paolo called Choque Cultural to find an artist who could help us channel our inner creativity. Pedro Jurubis took a mix-media approach combining paint, sketch and collage to visualize our ideas. He worked with the community members, and everyone drew their ideas.

Inclusivity and voice: Let everyone speak

Depending on the size of the group, you want to parcel activities so that everyone can participate and ensure all voices are heard. This is important, there is nothing worse than having to bottle up something you had to say, and leaving a place with the frustration of knowing you didn’t get a chance to say it. So, set some grounds rules for respectful discussion, but let everyone speak. To get around the size of our group, we mixed people and separated everyone up into groups of 5 or 6. Each group had a map, a facilitator and a few tools to help them map their local knowledge, ideas and visions for the future. At the end of the group exercise, we came together and each group presented their maps, and discussed among the other groups what common themes and thoughts had emerged. It doesn’t matter how many people attend, but its ideal to try and ensure you have as much diversity as possible. For example, though we had diversity in the types of people, we lacked diversity in geographies. We suffered a capture issue at our event. Though the invitation was completely open, we learned that most people who had attended, tended to live closer to the inner city. There were not very many participants from the neighborhoods along the periphery of the city. This is something we reflect on as we think about designing other such events.

Collaboration: Bringing diverse actors together encourages social learning

Cities are growing at a rate that’s alarming. The more they grow, the more complex they become, and the more difficult it is to manage and live in them sustainably. Ideally, most planners will tell you, that the key to making this complexity work for us is density. A huge opportunity to mix elements in cities like transportation, public services and neighborhoods that can make all of our footprints smaller and more sustainable. I am all for mixing, but I am one of the many that understands that mixing involves stepping outside of your comfort zones, accepting lifestyle change, making different personal choices and thinking in new and different ways. This can be a difficult thing for many of us who are habituated and comfortable in our current urban environments. Yet, it can be an incredibly rewarding exercise for city design. Too truly create viable transitions and sustainable enabling environments in cities to foster these kinds of changes, we need to go beyond just discussion about mixing elements, infrastructures and place in cities. Fundamentally, mixing has to be done at the ideation stage where inclusion and diversity in thinking and decision-making can be allowed to flourish. Not only will this move people to involve themselves and better accept and participate in sustainable changes, this collaboration will improve the outcome and make for more liveable and resilient cities. For example, when you put a doctor and an architect together in a room, suddenly a city building design is forever changed by the insight of the health professional along with the insight of the designer. Add an energy engineer and now the building is following energy efficiency standards. Add an artist and the building is likely to become more colorful, expressive and a source of cultural beauty, and inspiration. These are the kinds of collaborations and innovations you should be looking to push together when designing events and engagements with the public. Our societies are siloed, and we have all learned to work that way. We need to unlearn this. Each time we collaborate together on an issue, we encourage social learning and build an environment that facilitates collaboration in our cities. So, this century, this is our challenge. To reimagine our cities, what it means to be urban, and make our cities and ourselves more collaborative.