Wan-Yu Shih and Che-Wei Liu

Taipei

Edible urban gardens have gained increasing popularity in the Global North within the narrative of nature-based solutions for cities and as parts of urban green infrastructure, which reintroduce greenspaces and associated functions into built environments, with the aspiration of leading to a socially and ecologically more sustainable city. Amid the coronavirus outbreak, edible gardens have seemed to become an even more critical practice for cities experiencing lockdown, as food supply chains are upended and an edible garden plot close-by residents could enhance food security and mental health. Whilst Taiwan has so far successfully contained the pandemic, the Garden City programme (臺北田園城市計畫), which allocates small edible greenspaces to nearby citizens, might be viewed as a far-sighted policy in this kind.

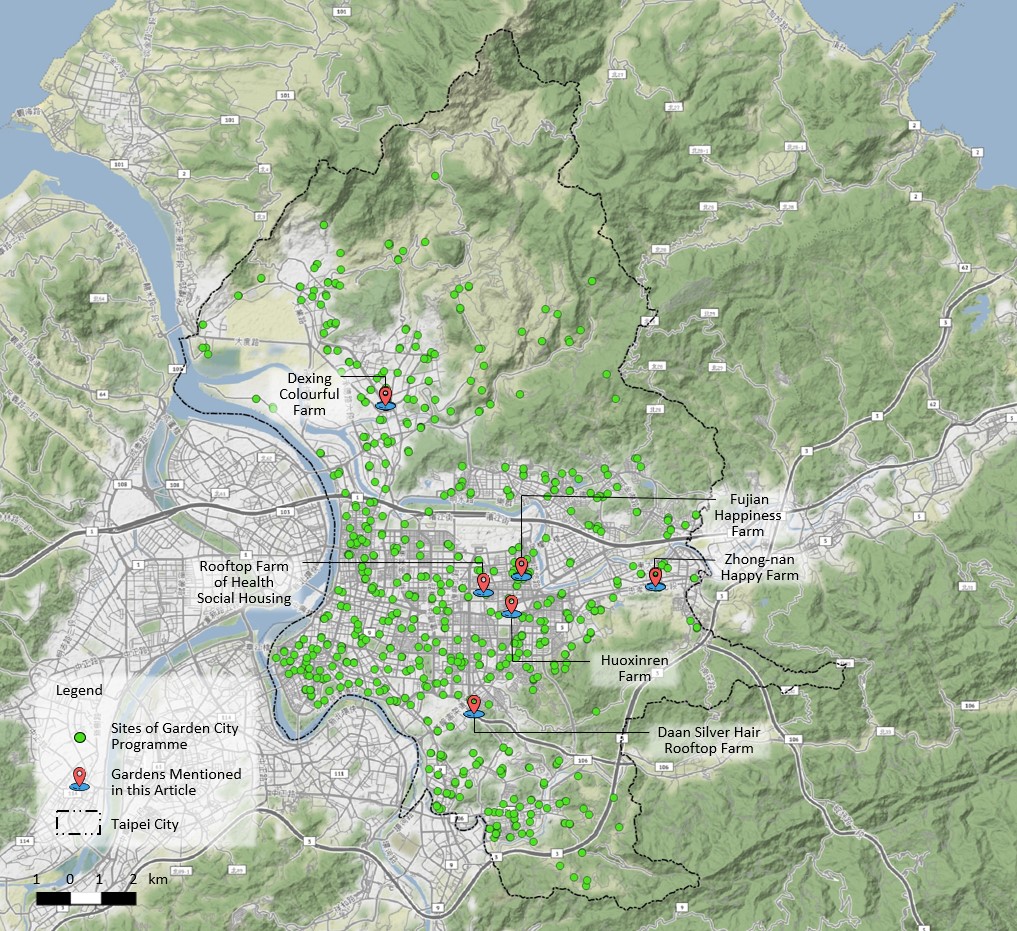

Whilst the programme is named after Howard’s “Garden City”, it is definitely not one of the followers of his spatial planning masterpieces. Rather, the ‘Garden City’ Programme in Taipei is a new type of urban farming that puts hundreds of small edible greenspaces into densely built-up areas to provide horticultural therapy, recreational opportunities, environmental education, and a breadth of social-environmental benefits through engaging citizens in food cultivation. The Taipei Garden City programme was officially launched in 2015 after a long incubation period of practices in local societies, which eventually formed a ‘Farming Urbanism Network (都市農耕網)’ and proposed a White Paper that was accepted by the current mayor – Ko Wen-je. Since then, the programme has rapidly integrated gardens from previous policy legacy, such as allotment systems, low-carbon community gardens, Taipei Beautiful sites, and Open Green sites, with newly established gardens both on the ground and on the top of the buildings. This forms 733 gardens across Taipei City within five years, covering 19.75 hectares and involving 54,013 citizens (as of Feb 2020).

Four main types of gardens have been included in the programme:

- Happy gardens (30%): the use of disused public lands for engaging local communities to plant vegetables and to maintain the site

- Green roofs (11%): the use of rooftop on public buildings for engaging surrounding communities to plant vegetables and to maintain the site

- School gardens (45%): the use of grounds and rooftops of schools (from primary to senior high schools) to engage teachers and students in environmental education

- Allotment gardens (14%): larger privately-owned lands that are designated as agriculture zones and were created long before the Garden City programme and are mostly located in the urban outskirts

Apart from allotments established at the city outskirt and school gardens using schoolyards and buildings, the first two types of gardens are often created in the most populated districts of Taipei, which provides great accessibility to the citizens. As most central districts of the city have a population density excess of 20,000 persons per km2, finding available lands within such compactly developed areas for farming is challenging, particularly for those on the ground. Several mechanisms have been adopted or developed alongside the programme to secure lands amongst buildings.

A critical strategy was to lift the ban on the use of vacant lands and buildings owned by the public sectors (both national and city governments). A throughout inventory of available lands across the city was conducted and published to enable site seekers to find a suitable land. This has resulted in several rooftop gardens on public buildings, such as district offices, social houses, and hospitals, as well as relatively large gardens at ground-level, such as Zhong-nan Happy Farm next to Nangang metro station and Fujian Happiness Farm. Whilst garden sites established via this scheme are free of charge, their food production is subject to not-for-profit restriction and only allows for self-consumption or donation.

Another scheme used to increase ground-level gardens is converting parts of the area inside a park, which has been officially zoned as parks and greenspaces in the city’s urban land use plan. This includes gardens, such as Huoxinren Farm at the Songshan Cultural and Creative Park, Hakka Farm at Hakka Cultural Park, and Dexing Colourful Farm at Dexing Park. Amongst them, the land of Dexing Park next to the SOGO department store was donated by Shihlin Electric as part of its corporate social responsibility activities while its factory location was re-zoned from industrial to commercial use. The process of re-zoning was, however, completed before the Taipei Garden City programme was enacted.

Attributing to these land acquirement mechanisms, which avoid the need of altering zoning and building codes in the urban plan and save time and budgets from land acquisition, the programme was efficiently implemented. However, the strategy inherent in the spirit of temporary use models of vacant lands from the previous policy – Taipei Beautiful programme, which incentivized temporary greenery on private vacant lands, is not without problems. One of the challenges is that many ground-level gardens sitting on government-owned lands, which are not zoned for greenspaces, are only temporarily available and subject to change for construction. The recent dispute on reclaiming the land of Fujian Happiness Farm for building social housing is one case in point.

“Happiness Farm” in the Fujian neighbourhood of Songsan District was created 7 years ago on a vacant lot owned by the Ministry of National Defence and was assigned as a garden city site under the Taipei Garden City Programme. The garden is located in the city centre, where the land is worth 20 billion $NTD, or 701,340,000 $USD (information based on the interview with warden). It has earned great popularity among local residents as a rare green space within the neighbourhoods to grow vegetables, to meet neighbours, and to ease symptoms of depression, and improve mental health. Over time the gardening activities also fostered good community coherence, as can be seen through the fast organisation of a self-help group when the community was informed to clear the place for social housing to be built by the National Housing and Urban Regeneration Centre. Although local residents keen on keeping this green space nearby, the land of the garden, which is officially zoned for residential use in the urban plan, provides little legal basis for their wishes. Unfortunately, this dispute won’t be the sole case. Sooner or later, many ground-level gardens will face the same problem.

Fostering social coherence and resilience amongst urban communities is one of the strengths of the Taipei Garden City programme. The temporary use of available lands to engage residents for farming activities has benefited the social-environmental ecosystem of urban communities. This function is however not sustainable, as current land use mechanisms cannot sustain long-term farming and so social coherence might fade out over time when the garden disappears. Like many cities opt to create urban farms on the rooftop in face of difficulty to acquire lands, Taipei City too pays attention to the top of the building to carry on the programme in the future. However, community gardens on the ground are generally more popular in the case of Taipei since it is visibly and physically more accessible by local communities. Conversely, the use of rooftop gardens is often constrained by safety concerns and building management. It should not assume that the social function of a ground-level garden can be equally replaceable by a rooftop counterpart.

Allocating doorstep green spaces from densely built urban areas is critical but challenging. It requires enormous efforts to negotiate and coordinate between public and private sectors. The success of Taipei Garden City programme so far in terms of implementation and popularity amongst citizens is attributable to the existence of a champion in the government to facilitate cross-sectoral collaboration as well as active local communities to cocreate and to realise the policy. Many popular gardens however might vanish due to its temporary nature of land use and the on-going densification of the city. The pandemic crisis is catalysing urban transformation to be a greener living environment that provides equal and accessible green spaces for public health and well-being. It is also an important time for urban planning to rethink the human-nature relationship while designing the legal mechanisms for not only land use zoning, but also a possibility for nearby residents to suggest a rezoning.